About

- Born at Seattle, Wash., 1954.

- Grew up in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of south Seattle.

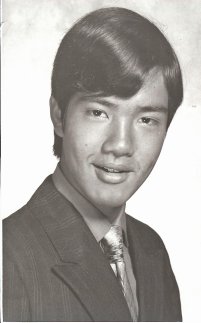

- Graduated from the University of Washington, 1976, Bachelor of Arts Degree, Communications.

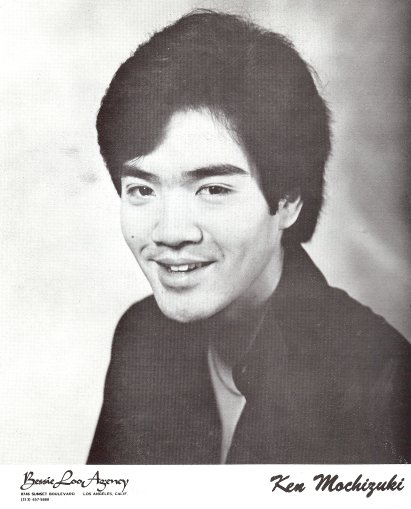

- Professional actor in Los Angeles, 1976-1981. Performed mostly on stage with a few screen roles, the most noticed being in an episode of “M*A*S*H.”

- Print journalist and free-lance writer for Seattle publications and national magazines, 1985-1996.

- Children’s book author and presenter, Asian Pacific American history author and presenter, 1991-. Presentations have included those at Purdue University, Northwestern University, University of Colorado at Boulder, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., and for the 1st Armored Division, U.S. Army, headquartered at Bad Kreuznach, Germany.

My Story

I was born in Seattle, Washington and my parents were also born there. My grandparents emigrated from Japan to the Seattle area around the beginning of the 20th century. In our household, we only spoke English, except when my parents spoke to my grandparents who knew only Japanese. But there was a grandmother who spoke pretty fluent English – a rarity for that generation. Because of the language barrier – and because I didn’t care at the time – I now consider it a significant loss for me that I was unable to communicate with my grandparents.

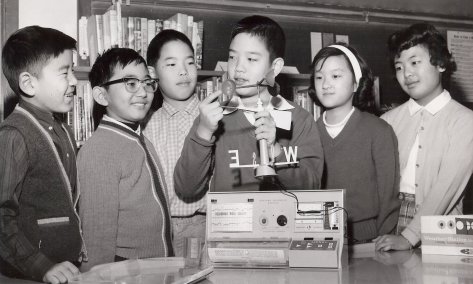

I grew up in the Beacon Hill area of south Seattle, and all the schools during the ’60s and early ’70s contained student populations that were about a third white, a third African American and a third Asian American and from families of all social/economic classes. Therefore, I am often perplexed that “multicultural education” is something taught when I received my multicultural education every day by just attending school. My father worked as a social worker and college instructor; my mother as a clerical worker. Along with my older and younger brother, we belonged to a local Methodist church and participated in its Boy Scout and youth groups, which occupied most of our time outside of school.

There was also a quarter acre of woods behind our house which I always played in, with or without friends that usually became the setting to play “war.” I am often asked about my favorite and most influential book while a child. I would have to admit that it was the set of World Book encyclopedias in our home. I ask students if they have done this: while flipping through the pages looking up a particular subject in the encyclopedia, they come upon and start reading other interesting subjects and eventually forget what they were looking up in the first place. With this ability to browse, encyclopedias in book form have the advantage over computer-based encyclopedias. I did a lot of that, fueling my interest in history – especially military history – and science, particularly astronomy and meteorology. My mother admonished that I should be reading more fiction.

Speaking of fiction, there is an incident that I still remember to this day. During fourth grade, our teacher was reading Charlotte’s Web to us, and during the morning of November 22, 1963 she read the chapter in which Charlotte the spider died. Of course, a collective sigh emitted from the entire class. My father sometimes picked my older brother and me up for lunch since we didn’t live far away from school, and when we left our school portable – our school was all portables – we noticed the American flag was at half mast. We asked our father why and he replied that President Kennedy “was shot.” When we arrived home, we saw the news that our president was dead. When I returned to my class, my classmates were abuzz about the assassination, and I told my teacher that both Charlotte the spider and our president dying during the same day was becoming difficult to accept.

And her profound reply: “That’s the value of fiction – it can sometimes prepare you for what happens in life.”

My first stab at creating fiction probably occurred around the campfires at night during those Boy Scout days. I liked to tell scary stories, and my effectiveness as a storyteller was measured by how effectively I scared others.

I would also have to admit that I learned more about storytelling through the mass media than books back then. Episodes of the ’60s TV series employed classic story structure: the beginning, middle, end, conflict, character arc, resolution. Each episode became a complete short story. My favorites were “The Twilight Zone,” “Combat,” a series that followed a squad of GIs in France during World War II, the original “Star Trek” and the original and intricately plotted “Mission: Impossible” – all watched on our black-and-white TV. Some pop music during the time told stories, particularly those in the folk genre. Emblematic of musical storytelling was “Sky Pilot” by Eric Burdon and The Animals which I consider the “Beowulf” of pop music since, as a powerful anti-war and atheist anthem, it tells an epic story in seven-and-a-half minutes.

Speaking of the ’60s, that had to be my definitive decade, as it was for the entire country. With the Vietnam War raging, the military draft affecting every family in America, the assassinations, riots in American cities, Americans landing on the moon, our country would never be the same. Comfortably secure in my middle-class home and early adolescent world, I tried to figure out what all the turmoil meant. My passion for music increased as I became intrigued by the lyrics of the likes of Simon and Garfunkel and particularly those of Jim Morrison, singer for The Doors. I sat before the stereo, transfixed by his dark but abstract, poetic lyrics – a musical Edgar Allan Poe.

A book genre I did get into was science fiction, becoming a fan of Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke – an interest no doubt fueled by America’s ongoing space program before reaching the moon. I received my real taste in creative writing in the ninth grade. My language arts teacher had his students keep a journal that he graded every week. To receive an “A” for the week, one would have to write 15 pages in the journal – it could be about anything. However, if one wrote with more of a journalistic approach – summary of a sports game, review, coverage of an event – one page of this type of writing would equal two pages, so seven-and-a-half pages would receive the “A.” However, if one engaged in creative writing – short story, play, poetry – that would equal three pages, with only five pages of creative writing required for the “A.” I thought five pages of fiction a week were easy. Not surprisingly, the subjects of my stories were mostly horror, spy stuff (James Bond was big back then, as he still is), and science fiction.

By the early ’70s, most teenagers on Beacon Hill became addicted to black soul music and could not help but be affected by the new “African American” identity. With their self-pride, search for their history, music, clothes and confidence, the African Americans inspired other groups, including the Asian students, to become “Asian Americans.” At Seattle’s Cleveland High School, I became involved in the Asian American cause and learned first-hand the cost of being the “radical” (an experience fictionalized in my novel, Beacon Hill Boys).

However, for me, high school was like stagnating in a still pond until I entered the University of Washington in 1972. It really was like being washed into the ocean. With protests against the war in Vietnam occurring on campus almost daily, I became exposed to a lot more people, a lot more ideas, and also learned how much I hadn’t learned in high school. I also grew more involved in the Asian American movement, becoming active in its student union and working on Seattle’s first Asian American newspaper, Asian Family Affair.

Always a film buff, I became entranced by film performances by some of the exciting young actors of the time such as Robert DeNiro, Al Pacino and Dustin Hoffman. I began acting in plays in theaters at the university and in Seattle. After graduating from the U.W. with a degree in communications in 1976, I made the momentous decision to try acting professionally and headed to Los Angeles.

Thus began some of the toughest years of my life. I spent most of my five years there with East/West Players, the oldest Asian American theater company in the country. Before I could support myself totally by acting, I worked as a bellman and waiter in a bankrupt hotel, delivered the Los Angeles Times in the middle of the night, delivered meat through the back doors of swanky Beverly Hills restaurants, even wired up disco lights.

There in L.A. I read the book that would set me on course to becoming a writer, even though I didn’t know it then. In college, I had heard a lot about the rediscovered novel, No-No Boy, regarded as the greatest work by an Asian American author. Originally published in 1957, the Japanese American protagonist is labeled a “No-No Boy” for the way he responded to a loyalty questionnaire while incarcerated in an American camp during World War II. Because his response included refusing to serve in the U.S. military, he spends time in federal prison and returns to his hometown Seattle, where he is ostracized not only by America at large immediately after the war, but also by his own Japanese American community for the political stand he took.

When I reached the last page, I was blown away. Not only from the power of the words, but also the power of his truth, that Seattle author John Okada dared to portray Japanese Americans in a realistic and often unflattering way. More importantly, his one and only novel told me that we can write our own stories, that we can write our own versions of ourselves.

From experience, I learned that every negative anecdote about the Hollywood entertainment industry is true. Working mostly on stage, I did land a few minor screen roles. And since most screen actors are unemployed 95 percent of the time, what my fellow Asian American actors did was, if a popular novel came out with Asian characters in it, we would read it in case the novel was turned into a film and we auditioned for roles in it. I also began reading the classic works by the likes of Hemingway, Steinbeck, Salinger and Conrad that I should’ve read in high school and college but never did. An actor/writer friend gave me a typewriter (remember those?) and dared me to write something of my own. A playwright at the theater also served as my mentor. And as I sat in a canvas director’s chair in my L.A. apartment, with a step stool as the typewriter’s table and a cardboard box acting as another table, I began what would become Beacon Hill Boys.

By 1981, I decided to be a writer instead. So, I packed up everything I owned in my Toyota Corona (When’s the last time you saw a Toyota Corona?) and made the 23-hour drive back to Seattle. I wondered if returning was a mistake since I came back in the midst of a national economic recession and jobs were hard to find. I again worked my variety of jobs: telemarketer, digging crawl spaces beneath houses, a cameraman’s assistant for TV news, a microfilmer for the federal National Archives.

If I wanted to become a writer, I had to teach myself how to write. Thus began my career as a journalist, mostly with Seattle Asian American community newspapers, for about the next 10 years.

As I tell students, being a newspaper journalist was good training to become a picture book writer, since both need to know how to say the most with the least amount of words. My goal was to become an adult fiction author at the time, but then I received that phone call during the summer of ’91 (see the “Books” section). The rest, as they say, is history.

Since 1993 with the publication of Baseball Saved Us, I have conducted over 100 presentations about my books and work as an author at schools, libraries, librarian and educators’ conferences, community centers all over the country – most of the towns and cities I have been to, I would’ve never been at any other way. One thing leads to another, as I have also served as a technical advisor for the film version of Snow Falling on Cedars, and was invited by the U.S. Army’s 1st Armored Division to conduct presentations at its bases in Germany about the history of Asian Pacific Americans in the U.S. military. I also wrote the book (everything not music or music lyrics) for a stage musical adaption of Baseball Saved Us.

Finally: no one gets to where they want to go without assistance from someone else, even though one might not realize it. For me, my trail was already there waiting for me, the door was already opened, by the late, great children’s author Yoshiko Uchida. During the late ’40s, when anything Japanese and anybody of Japanese descent were not popular in America, she still had the courage to write children’s books about Japanese subjects, with the help of an equally courageous publisher, and later about her own experience in the incarceration camps for Japanese Americans during World War II. She came before me.

If she were still around, I would like to tell her: “Thanks for helping to make my dream come true.”

A more extensive autobiography can be found in Something about the Author Autobiography Series, Volume 22, Gale Research, 1996